Duffus Castle stands in open countryside 1½ miles south east of Duffus, 3 miles south west of Lossiemouth, and 3 miles north west of Elgin. It is a superbly complete and well preserved example of a motte and bailey castle and as a result is worth travelling well out of your way to see. At the start of the 1100s, Moray was governed by the Óengus, the Mormaer (or "Earl") of Moray. Óengus was a descendent of Macbeth and in 1130 led a rebellion against King David I of Scotland with the aim of gaining more independence for Moray from the control of the Scottish crown. The rebellion was defeated and Óengus was killed, but it brought home to David the fragility of his hold over Moray.

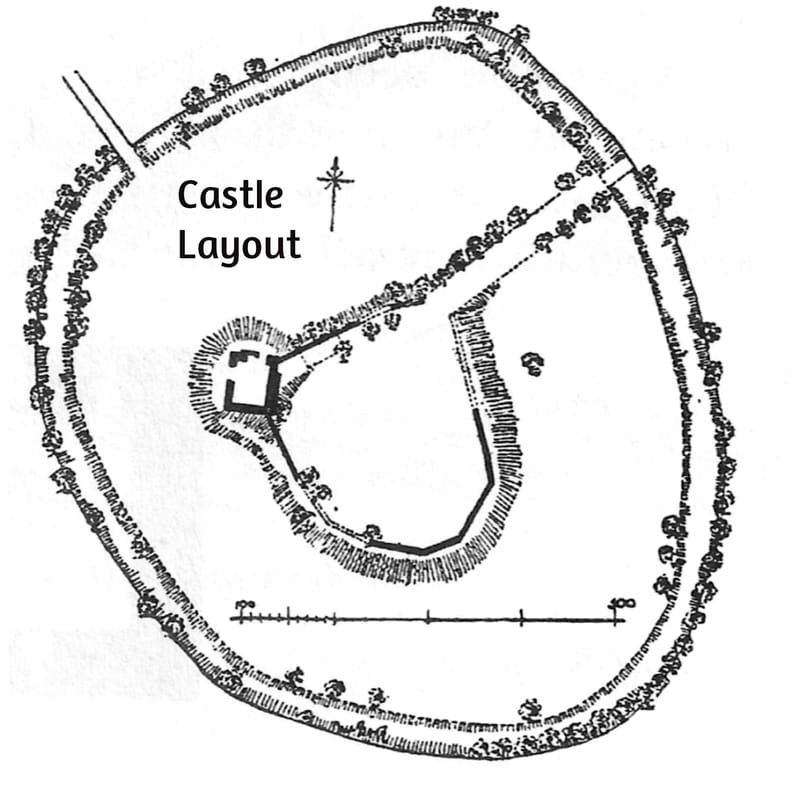

He responded by granting estates in Moray to men he could trust who, in return, were expected to maintain the "king's peace". Many were immigrants of Anglo-Norman or Flemish origin and one of these was Hugh de Freskyn (or Freskin), a Flemish immigrant who already held estates around Strathbrock (now Uphall) in West Lothian and who, presumably, had demonstrated his loyalty to David. Hugh de Freskyn decided to secure his hold on his new estates in what was probably a fairly hostile part of the country by building a stronghold. The result was the first Duffus Castle, built some time before 1150, the year in which King David I stayed at the castle while arranging for the building of nearby Kinloss Abbey. De Freskyn's first castle adopted what at the time was a very common pattern of a motte and bailey. On a low lying site convenient for the coast and for Elgin, de Freskyn oversaw the construction of a huge artificial mound, or motte, surrounded by a ditch. On top of the motte he constructed a timber keep, while the outer edge of the top of the motte would have been protected by a wooden palisade. To the east of the motte, and separated from it by a deep ditch, was a much more extensive, but lower, raised area known as the bailey. The edges of this lower mound would also have been protected by a wooden palisade, and this would have surrounded the kitchens, stables, barracks and other domestic buildings of the castle. Access to the castle would have been via a gate in the bailey, probably at its east end furthest from the motte. The only way into the "high security" motte would have been from the bailey. De Freskyn's son William had the grant of the Moray estates confirmed by King Malcolm IV in 1160. He responded by taking the family name "de Moravia", which much later simply became "Murray". In about 1270 the castle and estates passed by marriage to Sir Reginald Cheyne. In the wars of independence between Scotland and England, Cheyne was a supporter of Edward I of England and held the castle for him. It was attacked and destroyed by the Scots led by Andrew Murray in 1297, during the campaign that culminated at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. It was again captured by Robert the Bruce in 1307. In 1350 Duffus Castle changed hands once more, again by marriage: this time the new laird was Nicholas Sutherland, second son of the 4th Earl of Sutherland, and a distant descendent of Freskyn. The Sutherlands of Duffus would retain ownership of the castle for over 350 years until 1705. At some point in the 1300s the wooden motte and bailey castle was rebuilt in stone. It is not certain exactly when this happened. We do know that following the damage inflicted in 1297 the castle was being repaired in 1305 by Sir Reginald Cheyne with the assistance of a grant from Edward I of 200 oak trees. We don't know whether Cheyne rebuilt the castle in stone using the trees for flooring and roofing, or in wood: nor what state it was in when attacked in 1307. If Cheyne rebuilt in wood, then it was probably Nicholas Sutherland who built the core of the stone castle you see today after 1350. Either way, by the late 1300s the area of the motte was largely occupied by a massive two storey stone tower. A stone curtain wall surrounded the upper edge of the area of the bailey. After the castle was attacked again in 1452, a range of stone buildings, including a large hall, was built to the west of the tower along the north edge of the bailey. The main gate stood at the east end of the castle, and a paved road ran along the front of the range of buildings, out of the gate, and over a stone bridge that crossed the surrounding ditch. In 1689 John Graham of Claverhouse, Viscount Dundee, was a dinner guest of James Sutherland, 2nd Lord Duffus, at Duffus Castle during the first Jacobite uprising, and shortly before Dundee's death at the Battle of Killiecrankie. On the death of the 2nd Lord Duffus in 1705 the family decided that it would be more comfortable to live at their newly built Duffus House, and the castle was abandoned. Visitors today approach from the north and park in the nearby car park before crossing a bridge over the surrounding ditch and approaching the castle. What is truly amazing is just how much of it is still there. Large parts of the tower and the curtain walls remain, as does the base of the road out of the castle and the stone bridge over the ditch on that side. It isn't clear why only the buildings of the east range seem to have been robbed of their stone and so much of the rest of the castle has survived. There's a second mystery about the state of the stonework at Duffus Castle. The original artificial motte and bailey were intended to support the weight of wooden walls and buildings. Reusing them to support massive stone towers and walls might seem to be asking for trouble: and it was. As you approach the castle from the car park, it is clear that part of the structure has collapsed. When you enter the tower itself, you realise that at some point a large part of the north corner of the tower has simply slipped part of the way down the side of the motte, where it stopped, leaning over at an impossible angle. Meanwhile, it doesn't take great powers of observation to realise that parts of the curtain wall on the south east side of the bailey are leaning outwards at an unlikely angle. No-one knows when the collapse of the tower took place, but it is possible to see other parts of the tower where major cracks and slips have been repaired. The best theory is that the tower collapse might have happened as early as the 1400s, and the tower was abandoned as a viable part of the castle thereafter: perhaps the stone east range in the bailey was intended to be a replacement. Visitors to Duffus Castle will quickly become aware that this ancient military site has some very modern military neighbours. The end of the runway at RAF Lossiemouth is only three quarters of a mile to the north east, so visitors to the castle can be assured of a steady stream of military aircraft passing over as they land or take off.

Text Copyright Undiscovered Scotland © 2000-2021 https://www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk/duffus/duffuscastle/index.html